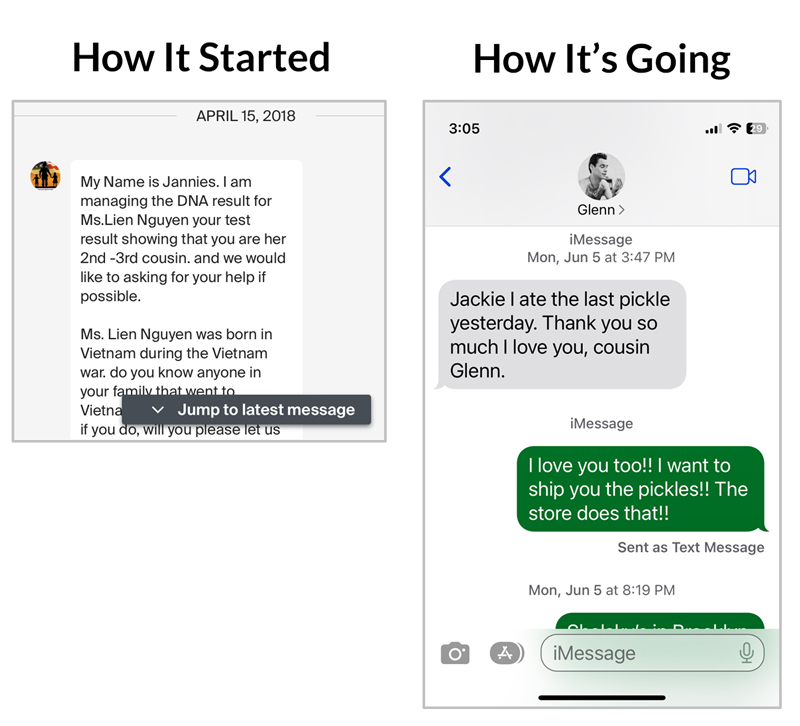

In April 2018 I got a notification through Ancestry.com announcing a new 2nd cousin DNA match. The graphic accompanying the match was unlike any I’d gotten in the years since I’d joined Ancestry, in that this new cousin was half Vietnamese. Its arrival, and the message that soon followed it, set off a years-long odyssey that brought me together with relatives I’d never known of–one of them a Vietnamese woman searching for her American Vietnam vet father–who were united by a thread of shared DNA on my father’s side that I can trace back to Austria and Poland in 1800.

The message I received was written by an Amerasian named Jannies, who was writing on behalf of her friend, Lien, who was identified by Ancestry as my second cousin. Jannies asked on behalf of my cousin if anyone in my family had served in Vietnam in 1968. I didn’t know which side of my family Lien could be connected with– maternal or paternal–but in either case, no one I knew of on either side had served in Vietnam. My parents had both passed away, as had most of the older generation on both sides, but I checked with the few relatives who might have known an answer to this question, and all agreed that there were no relatives who had served in Vietnam. I wrote back to Jannies saying I was really sorry, but I knew of no one in my family who served in Vietnam.

Jannies explained that Lien wanted to find her father so that she, her husband, and youngest child could move to the United States through the Amerasian Homecoming Act/Immigration Act, passed by Congress in the late 1980s, which required that the Vietnamese child of a U.S. war veteran prove paternity via a blood test performed in an approved government lab. The potential father had to agree to be tested. With many Vietnam Vets entering their 70s and 80s, Lien was worried that her father, should she find him, might have already passed away or soon would. “Lien is an orphan from the day she was born,” her friend Jannies wrote. “Amerasians’ life in Vietnam was very bad. They looked at us as the enemy. We got beat up everyday at school, told we were children of the enemy. Some were not allowed to go to school. Some of us were killed, and many more bad things. It was a very painful childhood, any bad thing you can name, we have been through it all and now we carry the scars in us.” I wanted to help Lien in her quest to find her father, but I’d hit a dead end. When Jannies contacted me again a month or so later asking me if anything had changed, I regretfully repeated that I still could not help Lien find her father.

A “Like” from a West Coast Syrop

One day some months later, I noticed someone named Jeff Syrop had “liked” a photo on an Instagram account I also followed. “Who are you?” I messaged him. He wrote back saying he was “not a blood Syrop,” but had been adopted by his stepfather, Leroy Syrop, and taken his last name when Leroy married Jeff’s mother. Leroy had adopted Jeff and Jeff’s brother and also later had a biological son with Jeff’s mother. Jeff had grown up in, and still lived in, California. I was stunned, because the very same Leroy Syrop had emailed me back in the mid-1990s when the internet was first becoming widely used, searching for people with the last name Syrop. Leroy had been born in the Bronx, where my father had been born and grew up, but then his family moved to Coney Island and eventually out west, and he wanted to talk to any of us who knew about all the relatives he had known back in the Bronx. He said he’d known some of my father’s relatives, and he even called my father’s mother Dorothy, who was at that time still alive and in her 90s, because she was the last of generation who might know his parents’ generation.

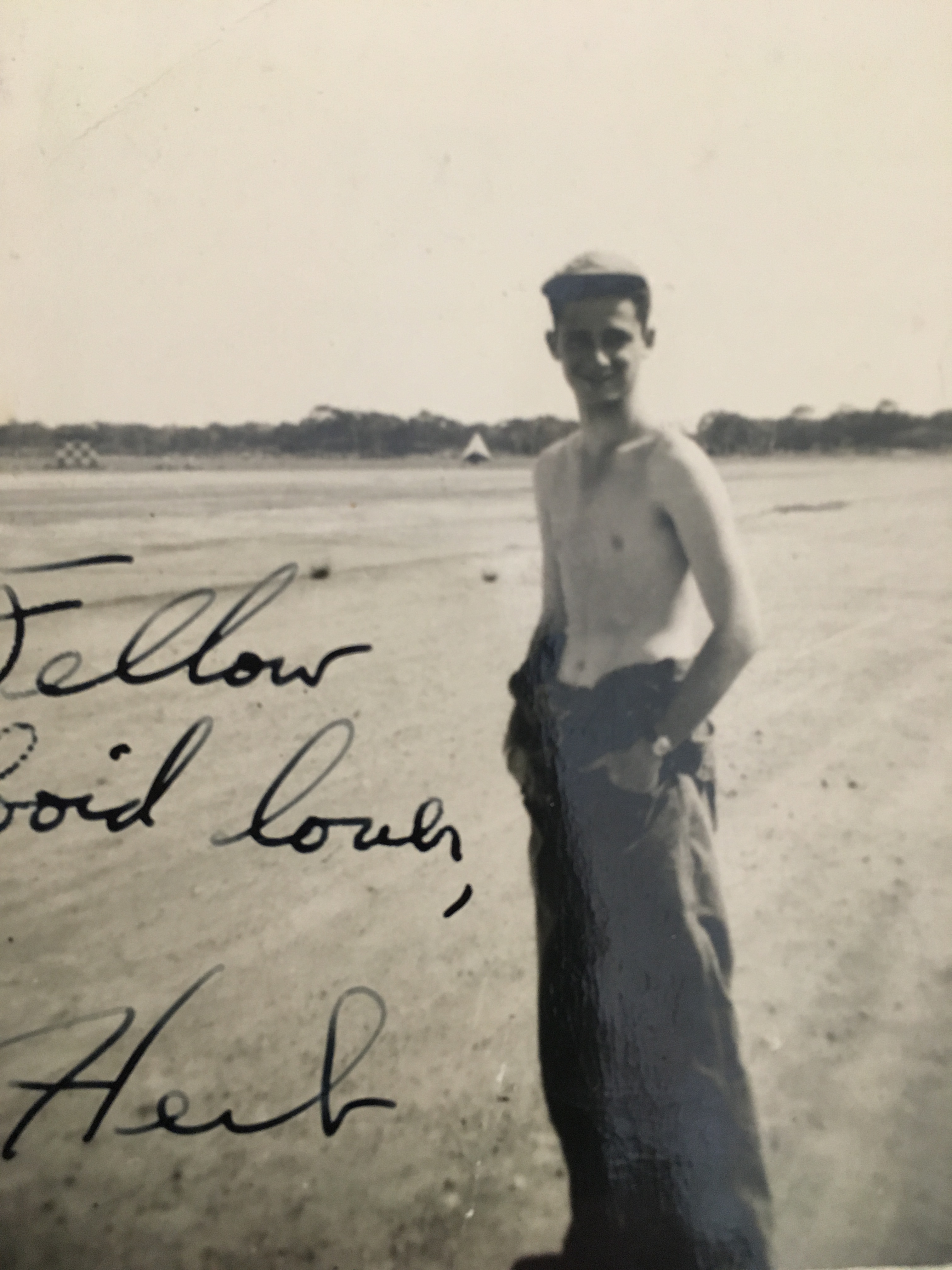

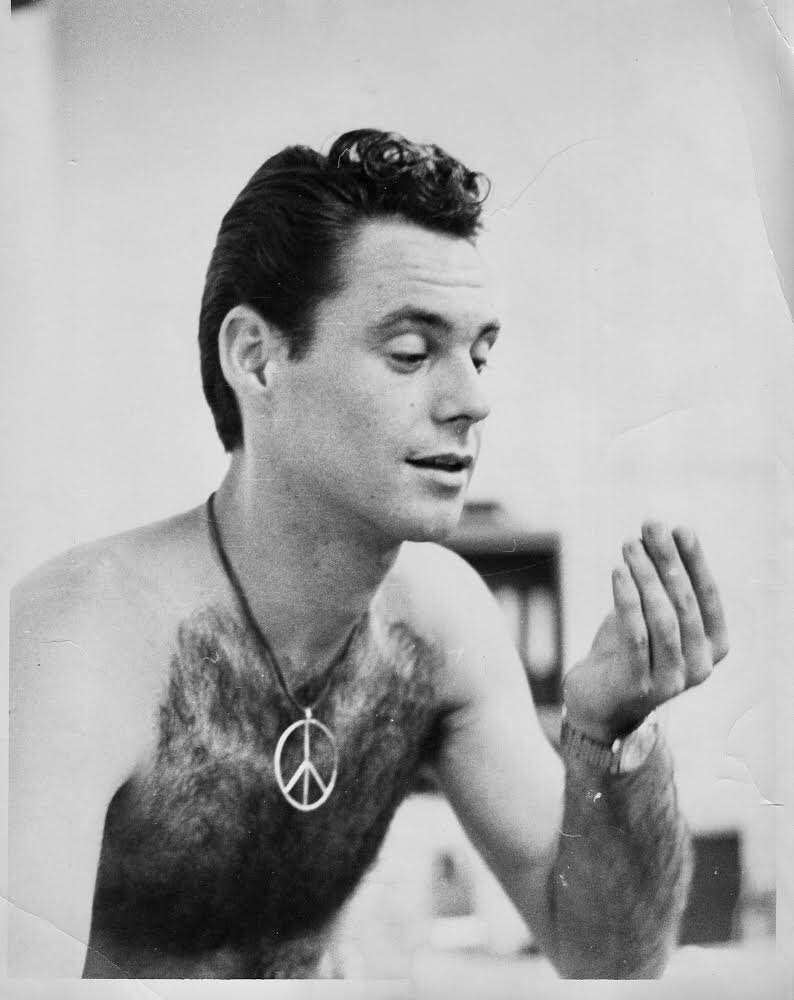

I asked Jeff if any of the West Coast Syrops had served in Vietnam in 1968, and he immediately replied, “Yes, my uncle Glenn, Leroy’s younger brother, was in Vietnam in 1968.” He’d been a Sergeant in the Air Force, and was stationed in Saigon, where he repaired electronic equipment and radios. Jeff said that a Vietnamese woman named Ko Fung had lived with Glenn in his apartment in Saigon, and that Glenn had loved and wanted to marry her, but didn’t because his brother Leroy had advised him against it. When the Air Force had shipped him back to the states exactly one year after he’d arrived, he left Vietnam never knowing his girlfriend was pregnant.

Lien’s mother had given her up 5 days after birth, as was common because Amerasian children were considered signs of collusion with the enemy. Lien never knew anything about her mother and moved from one foster home to another as a young child. She was eventually adopted by a Vietnamese family. Lien never knew who her biological mother or her father were. Until she had her own children, she’d never met a blood relative. In Vietnam, paternity is a very important part of status in society and even the language stresses paternal connections. Understandably, she was intensely committed to finding her biological father. Upon receiving Jeff’s news, Jannies wrote, “Your information gives us hope, a hope that a lost child who wishes to have love and a family will have a family that she belongs to. A family that understands who we are and where we are coming from.”

The Odyssey Begins

Jeff’s information about his uncle Glenn set off over a year of drama. Jeff spent many weeks trying to convince his uncle to do a DNA test on Ancestry.com to see if Lien showed up as his daughter. If the test showed no relationship, the whole matter would disappear. Glenn was already in his mid-70s and not in the best of physical and mental health. Though Lien was devastated at the idea that her father was not willing to have her in his life, to allow her to care for the only parent she might ever meet, she volunteered to sign any paper saying Glenn had absolutely no financial or other obligations to her. If he wanted nothing to do with her, she wanted only to prove his paternity so she and her husband and youngest child could emigrate here. “I will NEVER expect or need ANYTHING from you except for this one simple test of paternity, no promises or document to sign, nothing else at all beside the test,” she wrote.

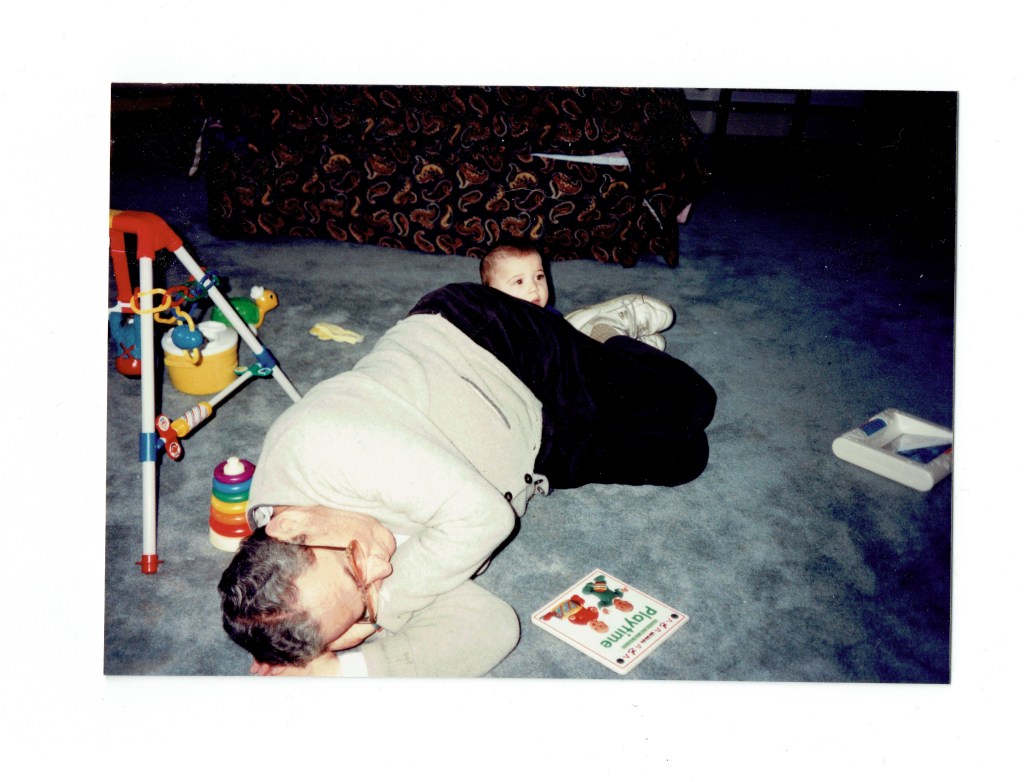

Unfortunately, Glenn’s brother Leroy steadfastly maintained that Glenn was the victim of a false paternity scam and advised him not to do the DNA test. Glenn’s relationship with his older brother Leroy was the strongest in his life. Leroy was 9 years older than Glenn and had been like a father to him in their turbulent, dysfunctional family. Glenn’s parents, Abraham and Rose, fought constantly and eventually separated. The young Glenn saw Abraham, one of my paternal grandfather’s younger brothers, standing in the doorway of the house he had previously lived in with Rose and their children, as he emptied a 5-shot revolver at Rose and her boyfriend, but he was too furious to shoot straight and missed every time. Glenn tried to keep his gun-toting father out of the house by holding the door shut, but his father overwhelmed him. The boyfriend tackled Abraham and broke one of his legs by slamming the door on it. Abraham did 2 years in San Quentin. But Glenn suffered from this and other violent episodes in his family and came to view his big brother Leroy as a mentor.

Because Leroy thought this was all a paternity scam and believed Lien’s story was untrue, he became angry and verbally nasty to us. Jeff, especially, who had looked up to his stepdad Leroy and had grown up with his uncle Glenn, could not believe the pushback we were getting. Believing deeply that logic would overcome all, he tried every which way to appeal to their logical minds but nothing worked. Things went south between Jeff and Glenn and Leroy, though they’d been close for many years. Jannies’ and Lien’s emails pressing the matter only inflamed matters, to the point that I asked them to hold off. I blocked Leroy’s and Glen’s emails for a period and tried to imagine a new approach to this problem.

Around this time, Jeff convinced his half-brother, Leroy’s biological son and Glenn’s nephew, to do an Ancestry.com test to prove that Lien was his first cousin, meaning that since Glenn was the only one of the Syrop brothers who went to Vietnam, Lien was his daughter. Sure enough, Lien showed up as his first cousin and I showed as his second cousin. Coincidentally, a new nephew of Glenn’s–who turned out to be the son of Glenn’s deceased younger brother, Jay–also turned up on Ancestry.com as related to Lien, Leroy’s biologic son, and me. (Jay’s son had previously been unknown to the family and they have since all met.) These new DNA results in his immediate family impressed Glenn, and he wrote to tell me that he was doing research on the leading DNA tests and how they worked.

Also around that time, Jeff put me in touch with Jimmy Miller, an Amerasian man who found his own Vietnam vet father years back, and who had become an activist for forgotten Amerasian children. Jimmy founded Amerasians without Borders, a great resource for Amerasians looking for their American servicemen fathers. He sent me a really powerful video about a Vietnam veteran in Yakima, Washington, who discovered, like Glenn, that he had left a daughter behind in Vietnam. The discovery had occurred when the Washington man’s American daughter had done a DNA test and was shocked to discover she had an Amerasian half-sister. The man in the video, like Glenn, had had a relationship with a local woman while he served in Vietnam, and like Glenn he was shipped out not knowing the woman was pregnant. I hoped that Glenn would identify with the veteran, who chose to meet his daughter in Vietnam and make her part of his life. It was such an amazing, emotional video and so easy to identify with the veteran and his daughter, so I sent a link for the video to Glenn hoping he would watch it in its entirety.

Because my own father had died only a month before I first heard about Lien, I was very much thinking about fathers and daughters. It saddened me that Lien had come so close to finding her father, which she had waited all her life to have happen, and Glenn was potentially going to let their relationship slip away. I wrote a very personal letter to Glenn about how it felt to lose my father and how much he had meant to me and how he had so shaped my life. I told Glenn that he was throwing away a chance to have a relationship with his only child, this daughter who wanted to care for him. I also said I wasn’t going to keep contacting him going forward if he refused to do the paternity test.

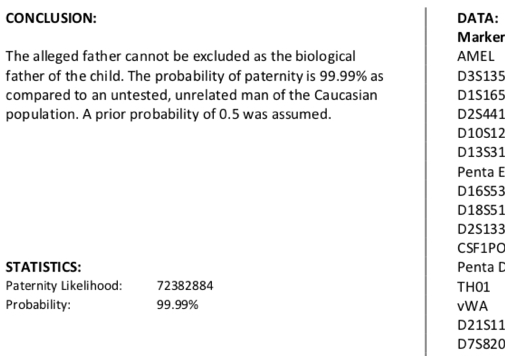

I didn’t expect to hear anything back, but several days later, Glenn emailed to say that he had made an appointment at the nearest approved lab to do the paternity test. I texted Jeff with the news and we both spent the day gobsmacked on two different coasts.

Only a day later–almost 1 year exactly since I’d first heard of Lien–Glenn received an email from the testing lab, and he forwarded it to me and his nephews.

“Do you know what this means?” Glenn asked all of us. Glenn’s nephew who had done that earlier DNA test responded, “Yes, I know what it means. It means that you are a father, a grandfather, and that you have a new nephew. Congratulations on your new family!” We all congratulated Glenn. “Do I give out cigars?” Glenn emailed back.

In his next email to family, friends, and some of his doctors, Glenn sent the news out and wrote, “Lien has my tenacious blood. I know now we will meet together, Vietnam or USA, father and daughter.” On the phone later, Glenn wept at the thought of how terrible his daughter’s childhood had been in Vietnam and how much he had to make up to her. But he was also terrified. “I don’t know how to be a father,” he said. “I will learn. I will do the right thing.” Glenn thought about all the suffering his daughter went through during her childhood, and how he hadn’t been there to help her for 50 years. He said he wanted to spend the rest of his life making things better for her and her family.

Here’s one of the emails Glenn sent to Lien and me:

Lien My dear Daughter,

My name is Tenacious for a reason!

I will help my daughter and her family at all costs. My daughter is the most important person in my life. Whatever she wants I will give her. I will help you in getting my two oldest grandchildren to the USA After you arrive in the United States.

We will work together like father and daughter.

You are the most important person in my life. I believe you have my tenacious blood.

Sending you all my love from my heart,

Your father.

💈Glen TENACIOUS Syrop

I wrote to Lien to ask her if she understood what had just happened. She always put everything into Google Translate, which sometimes produced less than stellar translations–but it was easy to understand the momentousness of what was now happening.

“Yes, Miss Jackie. I am very happy, because he called me his ‘daughter.’ That’s what I long for and look for. I also really understand my father’s personality. I understand he is a kind person, only misunderstanding makes him irritable. I was always patient and never blamed him. On the contrary, since I knew he was my father, I always loved him, though he did not recognize it. Dear Jackie, now the results have been rewarded. I understand you are also very happy for me, because you have tried so hard to get it. I think, I will try more to make my father happy. He has absolutely no errors, for the Vietnam War, he only made the arrangement of the United States. He was also not at fault for my birth, because he really loved my mother. I was really happy, when I found him, and was very proud of my father. Now, I apologize to my father, and hope he will have peaceful and happy days in old age. I will be very worried and scared if I hear a sad news about his health. I will be very sad, if in this life, I do not grasp his hand, to say “Daddy! I love you very much. ”

Once the embassy received the blood test results, Lien moved forward with her application to move to the United States with her husband and youngest daughter. Her older children would have to be sponsored later to visit the US. Lien was to get settled at first in Oklahoma, where Jannies lived, and where people would help the family get on their feet.

In mid-December 2019, Lien and her family flew from Vietnam to Los Angeles to meet Glenn for the first time at a hotel near the airport where they’d taken rooms for a night before Lien and her family flew on to Oklahoma. It was an emotional meeting for father and daughter. Glenn also met his youngest granddaughter and son in law, Thanh.

After she spent time settling in to this country in Oklahoma, Lien wanted to move close to Glenn and care for him. Some months later they visited Glenn for a week to see if they could line up work and places to live in Southern California. In 2021 Lien and her husband and daughter moved to be near Glenn.

A New Life

Over the several years since Lien came into Glenn’s life, Glenn has become the father he didn’t believe he could become. He has experienced a daughter’s love in a way that he never imagined, and of course it has transformed him. He’s enjoyed her devotion and constant concern for him, and he loves visits from his youngest granddaughter, who attends a Buddhist school. His son-in-law is quite possibly the most patient man I’ve ever met. Glenn has become the giving father and grandfather Jeff and I knew he could be but which he doubted.

Soon after arriving, Lien and her family put Glenn’s condo into tip-top shape (a huge undertaking). He no longer gets into trouble with the condo association for not maintaining the sidewalk and leaving a sink as sculpture along with an upside-down US flag on the patio. Lien brings him to her Buddhist temple for holidays, and his granddaughter and her friends visit him on school holidays.

When I speak with them on the phone, Lien frequently says, “DADDY!” and he corrects her English so she will improve. When Glenn uses spicy language, as he likes to do, she asks him to be more polite. He loves this.

As Lien once predicted, when Glenn settled into his new life with her and realized the role that Jeff had played, that rift between the two would heal. And it has. “Still, solving this problem was an interesting challenge in psychology and diplomacy,” Jeff told me. “I nominate you to be the next UN Secretary General.”

We Meet!

In May 2023, I met Glenn, Lien, and Thanh at our son’s wedding in Brooklyn. I marveled at the series of events, large and small, individual and global, that had occurred over centuries in order for me to be meeting my Amerasian cousin Lien (who calls me “sister”) and her father Glenn, neither of whom I’d ever met or even heard of until 6 years ago. The family tree I have been working on now includes Lien and Glenn, and it shows our common ancestors, as far back as my great-great-great grandfather Joseph Syrop (and his wife Rose), both born in Poland in 1800. Here’s the tree (for easier understanding, red boxes are drawn around the male Syrop relatives we have in common):

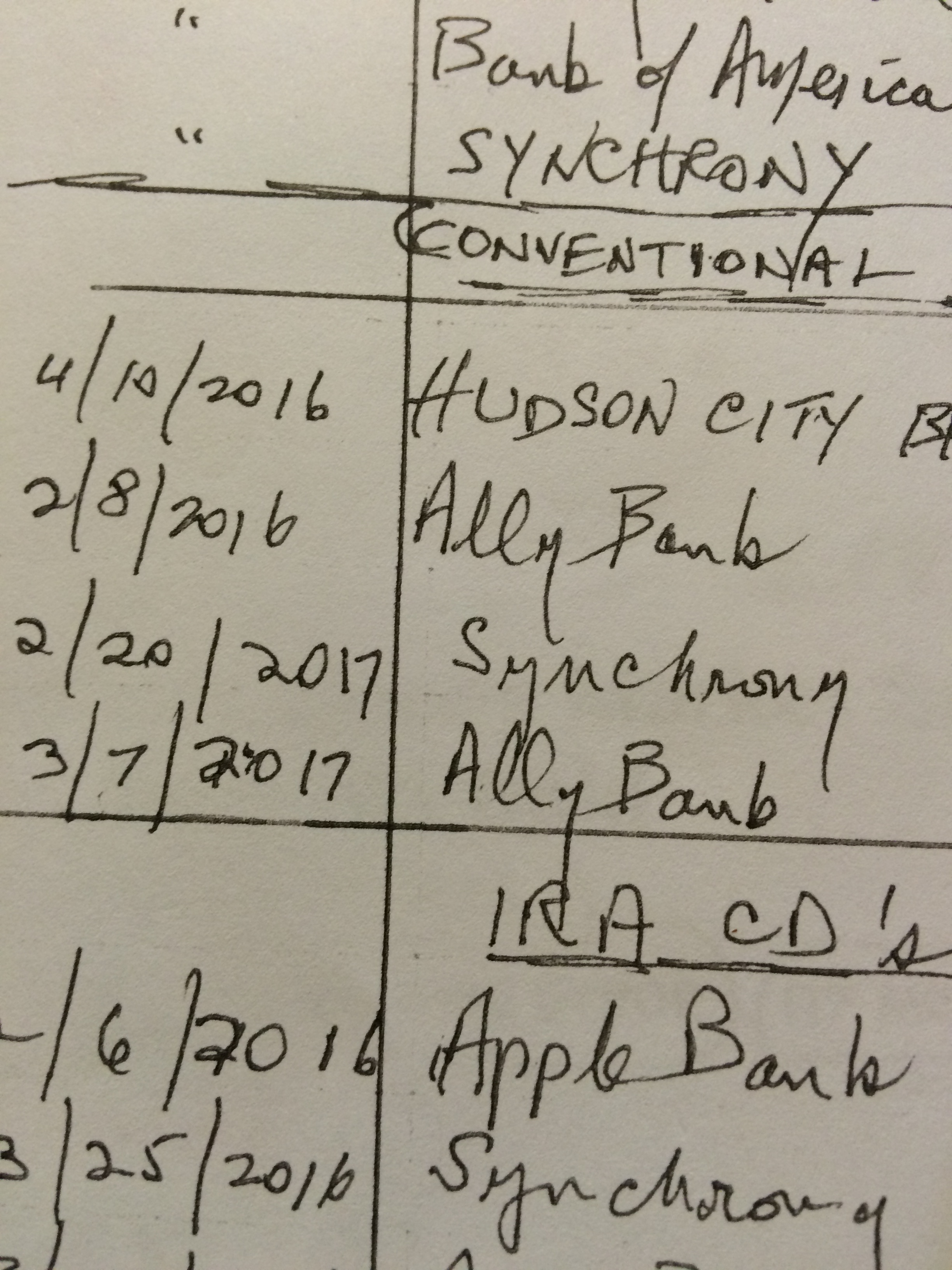

We also share my great-great-grandfather Abraham, born around 1829 in Poland. One of his and his wife Chaya’s many children was my great-grandfather Samuel Syrop, who was born in 1865 in Austria. Samuel Syrop seems to have ended up in Budapest running a beer hall before he and his brother Henry emigrated to New York City in 1881, where Samuel married another Austrian immigrant, Lena. Among their many children was my father’s dad, my grandpa Jack (for whom I am named) and Glenn’s father, Abraham.

I spent the day after the wedding with Glenn, Lien, and Thanh, ticking things off Glenn’s list of what he wanted to do in New York City. We took the subway (Glenn somehow managed to charm 4 or 5 fellow riders with his tales and pronouncements), bought pretzels from a vendor, walked to the Empire State Building, and finally took one of those open-top tourist buses around all of Manhattan. It was a gorgeous, sunny day and we had a wonderful time. Glenn was obsessing about whether he’d see rats (he didn’t but he discussed it with a lucky German tourist who had seen rats TWICE) or anyone urinating in public (he did not). And he told a young man with fashionably ripped jeans that in his day, ripped clothing meant you were poor. Miraculously, no incidents occurred.

We had dinner in their hotel room, a feast that revisited Glenn’s childhood foods: lox, bagels, cream cheese, and especially half-sour pickles. Lien was a good sport but she wasn’t really into the classic Jewish food. The half-sour pickles were Glenn’s favorite thing. He took the remains of the jar back to California on the plane to finish at home. I was sure that they would be confiscated at the airport, but two weeks later I received the text at the top of this piece: “Jackie, I ate the last pickle yesterday. Thank you so much, I love you! Cousin Glenn.” For his birthday in July, I sent him a big supply of half-sour pickles via Goldbelly so he could continue to enjoy them.

Vietnam

But Glenn had never met his two other grandchildren (and one great-grandchild) in Vietnam–Lien’s older children who were over 21 at the time of the petition were not able to be included under the Immigration Act). Even after spending months trying to enlist the help of two Congressional representatives, they were unable to get visas to visit Glenn here, and the wait is likely to be yearslong. Glenn grew more and more depressed because he believed he would die before meeting them, but Lien didn’t think he was healthy enough to make a trip to Vietnam. The long trip and his poor health made it a risky decision but Glenn was not to be dissuaded. “If I die there, so what,” he told me. So in January 2024, Glenn and Lien flew to Vietnam so he could meet his two other grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

The other day I called Glenn, and Lien said he was not in the house because he was at the complex’s Jacuzzi. Lien was able to tell me, in English, that she had gotten a date in December to take the US Citizenship test, and was studying for it weekly along with classes to improve her English. She is studying tenaciously. Because she is Glenn’s tenacious daughter.

Addendum: We have a new US citizen!

Linda Liên Syrop, December 18, 2024.

I wish to thank Elaine Paxson of Big World Design for all her help with blog crises and graphics.